The biggest handicap in research is an ability to think outside the box. The handicap is being encumbered by all the conventional wisdom in a given field.

– Aubrey de Grey

Bodybuilding is wrought with conventional wisdom. And what people believe makes someone look like a bodybuilder or fitness model is shrouded in misconceptions.

Setting aside the use of PED’s or other bodybuilding drugs; looking muscular, strong, shredded or fit is the result of a very specific set of circumstances. Circumstances EVERYONE has the ability to control.

Over the next three blog posts I’ll speak to these circumstances, uncover misconceptions, and provide some unconventional and counterintuitive training and nutrition methods of my own to maximize your development and enhance appearance. But before I do we need to come to a mutual understanding about something. And that something is…

Bodybuilding is an Illusion

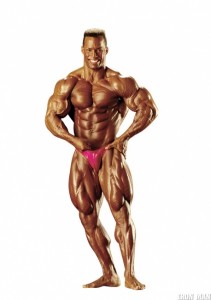

When I was a young lifter with aspirations of looking like Frank Zane and Shawn Ray I thought you simply built muscle to the point that your skin stretched to epic proportions, fat melted off of you and deep muscle separation was inevitable. In other words, you GREW into being completely JACKED.

You can imagine my disappointment and that of every teenage boy who ever thought the same thing when that didn’t happen.

So what did happen?

Well, muscle was built. Just not to epic proportions. And a degree of thickness was achieved that made it quite obvious (with a shirt on) that some heavy lifting had been going on.

And therein lies the rub…”with a shirt on”. Because with the shirt off neither I (at the time) nor 99% of those who lift weights resemble anything like the guy on the cover of Muscle & Fitness.

However, realizing how bodybuilding is an illusion can change all that.

The two key factors for creating the illusion of being enviously jacked are…

- Being as lean as possible.

- Retaining as much muscle as possible while at your leanest.

These two factors are very much controllable. That’s the good news.

The bad news is: Getting as lean as you’ll need to means that you are going to be fielding a lot of questions and concerns from your friends and family about your “health” because of how “skinny” you’ve become. They’ll tell you to stop whatever you’re doing. They’ll say you look terrible.

I say, don’t worry. It’s just jealousy!

In order to look how 99% of the population can’t you have to do what 99% of the population won’t.

Assuming that you are among the willing the question is, what do you do? This is where conventional bodybuilding wisdom enters the scene and attaches itself to you like a psychotic girlfriend. Despite the warning signs that she is absolutely nuts, for some reason you accept it and after a while you can’t seem to let go.

The road less traveled is often intimidating because it goes against convention. This is especially so in bodybuilding. Let’s look at what conventional wisdom says is necessary for superior physique development and see what we can offer as an unconventional or better alternative.

#1 –You Must Train Nearly Every Day and for Hours.

A commitment to training and a commitment to training with highest quality of effort possible are two different things. Plenty of people maintain their daily obligation to go to the gym and put in their 60-90 minutes of exercise.

But do they make progress?

In some cases, yes. In many cases, no. In the instances where they do make GAINZ the question is whether or not they NEED to put in that much time.

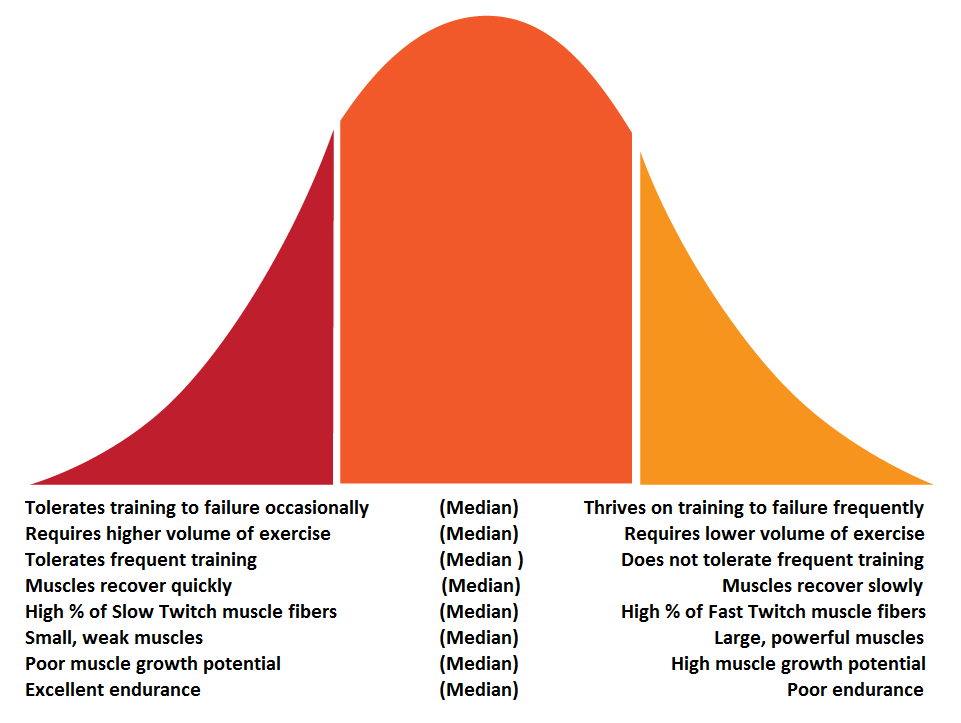

On average I spend just 2 hours training each week. There are times when I train more but they are infrequent. I am far from genetically gifted. Yet despite spending half to one-third the time training as most natural bodybuilders I’ve still been able to make consistent improvements and compete at a high level for 15+ years.

This is NOT an indictment of high-volume and high-frequency training—whose supporters are likely foaming at the mouth like an attack dog ready to pounce on me right now. Nor should the high-intensity crowd think I’m lending support to their minimalist approach.

It’s prudent for all factions to recognize the benefits provided by the other training methods and think about what parts they can pilfer and use to their own benefit.

The Unconventional Approach…

- Focus on Quality over Quantity.

- Training too or near muscular failure (1 rep shy) 80-90% of the time.

- Perform the highest volume of work (sets and reps) in the shortest time possible. However, this doesn’t mean perform reps at hyper-speed. Use a cadence of 2-4 seconds on the positive and 3-5 seconds on the negative to maintain constant tension on the muscles.

- Push your boundaries not only by lifting heavier weight or performing more reps but by manipulating ALL training variables.

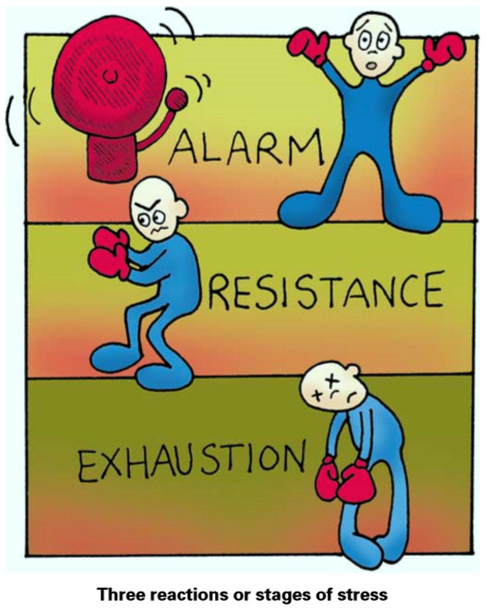

- Recognize that exercise is a negative stress on the body and only serves as a stimulus for muscle hypertrophy; lending to the importance of ample recovery time.

- Keep workouts to 20-45 minutes. (Eliminate time spent socializing and taking selfies and this shouldn’t be problem).

- An average of 3-4 workouts/week.

- Train each muscle group once every 3-5 days.

By no means am I implying that my training will produce dramatically greater results than training with less intensity and longer. I am simply pointing out that the common BELIEFS regarding how much time must be dedicated to looking like a bodybuilder is severely misunderstood.

For me the big picture is all about managing and manipulating training demands to stimulate muscle growth and strength at each stage of a person’s life. That means understanding how exercise fits within the schema of every other stress and activity a person is faced with and how to navigate the waters to help them reach their goals.

For me the big picture is all about managing and manipulating training demands to stimulate muscle growth and strength at each stage of a person’s life. That means understanding how exercise fits within the schema of every other stress and activity a person is faced with and how to navigate the waters to help them reach their goals. I was asked to write the forward for his book Muscle Explosion a few years back and the one thing I noted is that even though his training programs look bat shit crazy (and I mean that in a complimentary way), he is very calculated in his approach. He sees the big picture and then goes nuts mapping out the details.

I was asked to write the forward for his book Muscle Explosion a few years back and the one thing I noted is that even though his training programs look bat shit crazy (and I mean that in a complimentary way), he is very calculated in his approach. He sees the big picture and then goes nuts mapping out the details. If you’re not getting the result you want, reexamine the details and your application of them or adopt a new philosophy. Don’t jump on every new program or abandon what’s worked for each compelling piece of new information. Not without planning for it so you can determine its true worth and relevance to the big picture.

If you’re not getting the result you want, reexamine the details and your application of them or adopt a new philosophy. Don’t jump on every new program or abandon what’s worked for each compelling piece of new information. Not without planning for it so you can determine its true worth and relevance to the big picture. While some of these things are the stimuli for why we succumb to our impulses, experts agree that

While some of these things are the stimuli for why we succumb to our impulses, experts agree that

I have nothing against “fitness experts.” In fact I regularly seek out, read, listen to, and pick the brains of people (not in a Walking Dead sort of way) that I consider to be experts in various areas of exercise because in quiet moments of self-reflection I realize that I don’t know it all. Hard to believe I know. I like hearing different points of view, especially the diametrically opposing ones. As Stephen Covey put it in The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, “seek to understand.” If I’m able to understand their point of view then I’ll either glean new insight and apply it to what I do, ooooooooor I’ll bang my head against a wall thirty-two times as a preventative measure to ensure the information doesn’t settle into my brain.

I have nothing against “fitness experts.” In fact I regularly seek out, read, listen to, and pick the brains of people (not in a Walking Dead sort of way) that I consider to be experts in various areas of exercise because in quiet moments of self-reflection I realize that I don’t know it all. Hard to believe I know. I like hearing different points of view, especially the diametrically opposing ones. As Stephen Covey put it in The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, “seek to understand.” If I’m able to understand their point of view then I’ll either glean new insight and apply it to what I do, ooooooooor I’ll bang my head against a wall thirty-two times as a preventative measure to ensure the information doesn’t settle into my brain.