Amass as much muscle as possible and present it as part of a symmetrical physique.

That is the bodybuilder’s creed. There is not much more to it than that. There is no bias, there are only results. Whatever will improve results will be heralded and whatever does not will be discarded.

Amid the heap of least effective training methods for bodybuilding stands Super Slow™ and its spin-offs.

Bodybuilders have for the most part shunned most forms of slow training but not for what would be considered the obvious reasons:

- The overwhelming discomfort brought about by the buildup of lactic acid.

- The boredom of moving as slow as a pregnant turtle (15-30 seconds to complete a single rep).

- The systemic drain (CNS fatigue) following each workout.

- Or the lack of “spice”.

The truth is, any dedicated bodybuilder will happily accept any by-products of a training method no matter how much discomfort or boredom it brings if the method helps him to attain larger, more fully developed muscles. In fact most bodybuilders learn to embrace those aspects of training that the average trainee is less likely to tolerate. It’s called commitment to your craft.

My early years as a competitive bodybuilder coincided with my discovery and the implementation of Super Slow™.

The workouts were excruciating, physically draining (leaving me lying on the floor for 15 minutes afterwards) and required a tremendous amount of mental toughness—and I embraced them for all of these reasons. Most bodybuilders I knew and still know today rarely train so hard they end up lying on the floor or praying to the porcelain God. Super Slow™ protocol also required just 1-2 workouts per week—something considered blasphemous within bodybuilding.

In my mind I was breaking the mold and would be living proof that the classic bodybuilding programs were nothing more than drivel. And that one could achieve equivalent results or better with Super Slow and equivalent programs.

If we isolate certain elements of slow training protocol, what’s being implied is quite rational based on exercise science.

Unfortunately when these singular elements are combined into what appears to be a logical protocol, what actually transpires does not fully reflect theory. At this juncture a bodybuilder who is more concerned with reality than theory will abandon such method in lieu of something that works, even if that something lacks a logical basis.

Where Super Slow™ and other slow training protocols stumble is in their extreme interpretation and implementation of exercise science principles.

For example it is completely rational to lift a weight slowly for the purpose of reducing momentum and the contribution of stored energy torque, increasing muscular tension, obtaining greater feel for the muscle(s) being targeted, and decreasing the risk of injury.

But is it necessary to take “moving slow” to the extreme of single repetitions that take upwards of 15-30 seconds to complete? More importantly is it truly beneficial to move this slowly? An analysis of several studies on repetition speed done by Chris Beardsley at Strength and Conditioning Research would indicate otherwise.

As with most things there comes a point where even a good thing can go bad if taken to an extreme.

Rep Speed

On average most slow training protocols have the trainee execute each movement with a 10/10 or a 10/5 cadence give or take 2-3 seconds based on the exercises range of motion. If working within the accepted time under tension (TUT) for hypertrophy (30-90 seconds) moving at the above cadence would equate to performing only 2-5 repetitions.

Although TUT is of great importance what happens within that TUT is of equal importance. More contractions mean, greater blood flow and interstitial fluid to the muscle fibers, increased mechanical work and protein synthesis, and less time for ATP replenishment and recovery of already worked muscle fibers, as well as activation of more satellite cells at the point of stretch.

Training Frequency

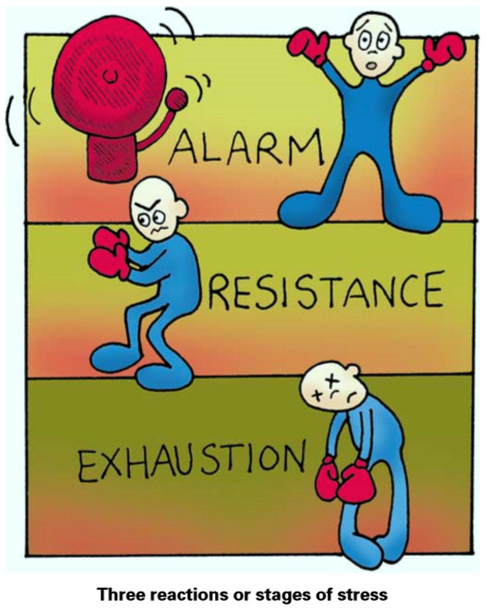

One thing I love about most super slow training methods is that they rightfully recognize the importance of balancing exercise stress and recovery. Most bodybuilders grossly overreach their recovery ability, resulting in perpetual stagnation. A periodic decrease in training frequency (and volume) would be a quick and easy remedy but it’s a remedy that often goes ignored for fear of being seen as less than hardcore.

However, the problem with many slow training models is they take the ‘stress/recovery archetype’ to the extreme of only 1-2 workouts each week sometimes less and rarely more.

For an individual experiencing a high degree of systemic stress from their training, as is common with Super Slow™ or any number of similar programs like Slow Burn™, such low frequency is necessary to allow for systemic recovery. One of the [many] drawbacks however is that less workouts means less protein turnover, and this is an important mechanism in maximizing muscle hypertrophy.

Variation

Slow training denounces the need for variation so most programs go unchanged for long periods. It’s true that for beginners and even some intermediates becoming proficient at performing their exercises is important in order to be effective at targeting the intended muscles. And for this reason it is best to stay with the same exercises until those skills are honed.

But for an advanced bodybuilder who already possesses a high degree of lifting proficiency executing the same exercises week-in-and-week-out on the same equipment in the same exact manner is wasteful. Being overly accustomed with an exercise diminishes its ability to disrupt homeostasis and give the muscles cause for adapting beyond their current development.

There are two other reasons why, as a bodybuilder, more variation in exercise selection is necessary—symmetry and detail.

When we talk about symmetry we are not only speaking about the balance of the upper and lower body or even the development of one muscle group compared to another—but the balance within a muscle group. Having an imbalance within a muscle group is not only an aesthetic problem but will often result in chronic injury.

It is not uncommon for a muscle to lack detail simply because certain points along that muscle have not fully developed. While it is no guarantee of “full development”, performing a variety of exercises at various angles ensures that a muscle will receive adequate stimulation along its entire length. No handful of exercises—even on the most bio-mechanically correct exercise machines as most slow training facilities boast to owning—can ensure complete and balanced development.

Overload and Progression

Slow training models only view overload through the lens of single or double progression, meaning an increase in weight lifted and/or the number of reps performed or TUT. Again, this is absolutely correct…for beginners and intermediates.

Overload is anything that adds to the burden of exercise. This means you can overload through an increase in volume, frequency, or intensity, or changing rep performance (i.e. increase or decrease in lifting tempo, Zone Training, 21’s, stage reps), adding set variables (i.e. forced reps, negatives), vary exercises, angles or equipment, as well as increasing weight load, reps, or TUT, or any combination of them all.

Focusing solely on strength gains at the advanced level of training or for the purpose of bodybuilding is ignoring the fact that increasing strength does not always necessitate an increase in size.

The Verdict

Bodybuilding is an endeavor that requires much attention to detail and constant fine-tuning. Individuals who pursue bodybuilding are not interested in average results.

Yes, very good results can be had performing only two half-hour training sessions per week. Personally, I rarely train more than two full hours in a week and neither do the majority of my clients. Quality does trump quantity, except when the quantity is less than optimal.

Speaking of optimal. From this article I intentionally left out the debate that goes on between slow training advocates, the High Intensity Training community and the rest of the resistance training world regarding whether performing one set to failure is optimal for muscle hypertrophy. The reason I left it out is because the answer is yes and no depending on a number of individual factors and factors related to program design and application that are too exhaustive to discuss here.

Though this article is not meant to bash those that perform Super Slow™ and similar training methods, I can’t help but to point to their inefficiencies for the purpose of bodybuilding and declare them inadequate for bodybuilders seeking the upper limits of muscular development.