Think variation and muscle confusion are one in the same? They’re not.

You cannot “confuse” or “trick” muscles into hypertrophy and strength gains. When you nestle under the bar there is no hesitancy or confusion on your muscles part about what they must do—which is contract. And if you’re doing it right, they’re contracting pretty frickin’ hard.

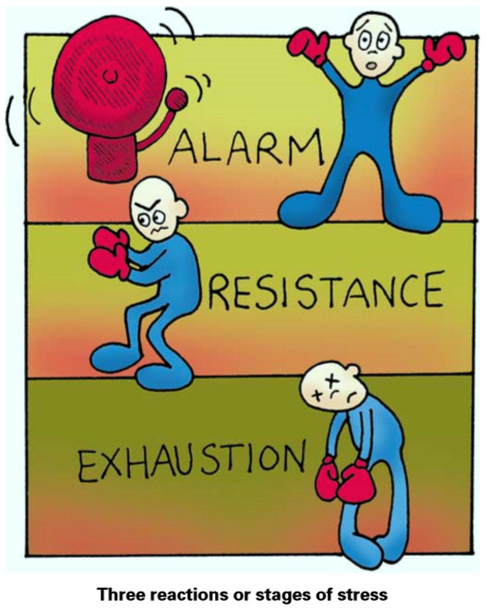

And when you work your muscles to exhaustion and finally call it quits, it’s crystal clear to them what needs to happen next. They need to adapt. It’s their evolutionary duty.

Hypertrophy and Strength Adaptations Result from Muscles being subjected to Specific Conditions.

The basic requirements for building muscle and strength are no secret. Challenge the muscles with relatively heavy loads, use enough volume to sufficiently exhaust mechanical and chemical resources, progressively increase training demands, repeat the process frequently enough to maintain and elicit new gains, but not so frequently that you inhibit recovery. Bam! That’s it!

Keeping up with these requirements as you develop more muscle and strength, in and of itself creates variation. But you and I know that is not the type of variation implied when fitness gurus speak of variation.

No, we’re told to switch things up. That we shouldn’t keep doing the same thing.

But exactly what does that mean?

Change some Elements—Don’t do an Overhaul

As pointed out, if the goal is muscle hypertrophy and strength gains there are certain conditions your training must meet. It’s what we refer to as the S.A.I.D. Principle—specific adaptation to imposed demands. In the same way, if your goal is to run a marathon your training must reflect the best means of improving aerobic output and muscular endurance.

The idea is not to keep your muscles “guessing” (they don’t sit around between workouts wondering what’s coming next) but to give them exactly what they need to get the result you’re looking for. If the foundation of your training remains intact and in alignment with your objective then varying some of the elements can help enhance results and circumvent plateaus.

The Many Faces of Exercise Variation

The elements we most commonly think of altering are the exercises, rep and set schemes, intensity, rep performance, and the type of workout. I’ll address each individually.

Exercises – Varying exercises can be anything from performing the same exercise at various angles (i.e. flat chest press, incline press, decline press), performing vastly different exercises for the same muscle group (i.e. leg extensions and sissy squats) or performing the same exercise using different equipment (i.e. barbell deadlifts vs. trap bar deadlifts or dumbbell curls vs. cable curls).

Those who implement a variety of exercises, cyclically, tend to have more well-rounded physiques with better balance between or within muscle groups. There is also a reduced risk of overuse injury (barring excessive volume or frequency) resulting from working in the same plane of motion over long periods.

Reps & Set Schemes – Increasing or decreasing your rep range, set length (Time Under Tension) or the number of sets performed is a play on volume. It’s a means of ensuring that all muscle fiber types (Type I, Type IIa, Type IIb) are subjected to the appropriate workload to maximize development.

It is also the easiest way to alter training demands. When your muscles acclimate to a particular workload an increase in volume is an effective means of challenging them to a higher level of conditioning. However, this increase in your total demands—which is necessary—will affect recovery ability.

Conversely, lowering your volume by performing fewer sets is effective in providing for more recovery time. Cycling between high, low, and moderate volume training affords you periods of heavy demands to stimulate gains and periods of lower demands to boost recovery and sensitize you to higher volume training.

Intensity – Just as with reps and sets, increasing your intensity of effort—by training to muscular failure or beyond—can heighten training demands and stimulate muscle hypertrophy and strength increases. Taken too far for too long it can also stifle recovery by exhausting your CNS which is why it should be implemented judiciously and cycled.

Rep Performance – Changing repetition speed and the execution of your reps (i.e. stutter reps, partials, Zone Training, 21’s, negatives, etc.) is a means of disrupting motor patterns, influencing fiber recruitment, and increasing training demands.

Watch this tutorial on Zone Training for an alternative way of performing your reps and check out the related article: The Pump, Occlusion Training, and How to Enhance Them.

Why would you want to disrupt motor patterns? After all, you’ve worked so hard to get your form right so you can properly target your muscles and handle the most amount of load safely, right?

The reason is, sometimes the adaption you get is not the one you want. We want to develop our muscles, we want them to get stronger—but not all of the increases in strength you see in the gym is the result of increased muscular development. The more practiced and technically sound you are at certain lifts the less energy and resources you will use to perform them.

If the end game is to thoroughly fatigue your muscles and give them cause for further development then performing exercises in a manner they are unaccustomed to can present a new set of demands to adapt to.

Research on repetition speed has shown that faster repetition may hold a slight advantage over slow reps in increasing strength but there is no statistical difference in the effect on muscle hypertrophy. However both fast and slow reps have several advantages and disadvantages. Watch this video for a breakdown of each.

Type of Workout – Different workouts lend themselves to different adaptations, this much is obvious. A trainee who performs several different modes of exercise or engages in various styles of training may have greater overall fitness than someone focused on only one mode with one objective. But they won’t necessarily excel or achieve their ideal level of development in any one area unless by genetic chance.

And this is where must be intentional about using blatantly different styles of exercise for variation versus altering the elements like mentioned previously. If you can accept the potential for regression in certain aspects of your development by abandoning one type of training or exercise for another then by all means, go for it.

The Final Word

I understand what the “muscle confusion” guys are getting at. The need for exercise variation is overwhelmingly valid. It just bugs the hell out of me—as well as every other sensible fitness instructor—when we have to explain to a neophyte that muscle confusion is nothing more than marketing bullshit.

Thanks for reading this far! If you found this information useful please share it.