Does it make me less of a tough guy because I prefer machines over free weights? Am I now required to relinquish my “Hardcore” membership card because of this admission? A mindless iron-pumper who’s never done a critical evaluation of machines versus free-weights will surely answer with a resounding yes. (He’s probably calling me a pussy too.)

I pay it no mind though. I still squat, deadlift, bench press, military press, do barbell rows and use dumbbells just as much as the hardcore. And I recommend you do too.

You see, I;m not here to lambast free-weights for all their imperfections nor do I view machines as being of superior value. I see value in both and thus implement both. When experts in either camp pits one against the other it displays their own fundamental misunderstanding of what matters when it comes to muscle hypertrophy.

It’s Not the Wand, It’s the Magician

If you think machines somehow do the work for you, you’re deluding yourself. If you think free-weights are always more demanding than machines you’re further deluding yourself.

How demanding an exercise is has more to do with how it’s being performed than the exercise itself. True, some exercises are inherently more demanding because the number of muscles involved and the complexities of the movement—think squats. But a set of heavy leg presses taken to the point of muscular failure or beyond can be just as demanding or more, than a set of heavy squats stopped a few reps short of failure as most of us do for safety reasons.

Hard versus Hard on the Muscles

If you train like a wimp—and by wimp I mean you terminate your sets just as the burn sets or always stop a couple of reps short of failure because you’re a cream puff—then free-weight exercises will feel harder than machines. As mentioned, free-weight exercises tend to have greater involvement of assistant movers and stabilizer muscles and this contributes to the overall systemic stress you experience. But don’t mistake the exercise feeling harder as actually being harder on the target muscles.

If your goal is muscle hypertrophy then maximizing the mechanical tension and cellular fatigue (metabolic stress) of the muscles being targeted should be your focus. Dispersing muscular tension amongst multiple muscle groups diminishes what’s experienced by the target muscles.

This leads to the primary reason I find machines more beneficial than the conventional bodybuilder.

Pain as a Rite of Passage

Creating an environment wrought with deep cellular fatigue and metabolic stress is not fun. It’s typically accompanied by a degree of muscular burning equal to being branded with a 1300°F iron. (Okay, maybe not that bad but if feels like it 3/4 of the way through leg extensions.)

The discomfort is just part of the process. It’s the price we pay for “Gainzzzzzz” as every meathead lifter (male and female) likes to say these days. …I love you all BTW.

Creating the aforementioned environment is more easily accomplished using machines which is why I’m not just the machine club president but I’m also a client. For all the great benefits big compound free-weight exercises give us the one drawback is that the weakest muscle group gets worked the hardest.

In order to balance the scales of muscle stimulation, exercises that help isolate each muscle group are necessary. Properly designed machines help to nullify weak points and maintain constant tension on the target muscles…

But Not all Machines are Created Equal

Shout-out to my good friend and groomsmen at my wedding, Mark Houghton, who posted this study to my Facebook wall: EFFECTIVENESS OF ELBOW FLEXORS TRAINING ON MACHINE WITH VARIABLE-CAM AND DISC

Karczewska, M., Urbanik, C., Madej, A., Iwańska, D., Staniszewski, M., Mastalerz, A. Jozef Pilsudski University of Physical Education in Warsaw.

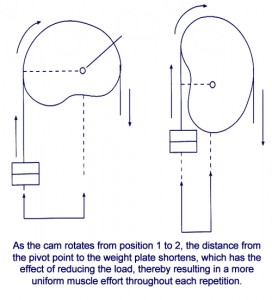

The researchers of this study compared biceps training on machines with a variable resistance cam (ala Nautilus) whereby the resistance changes relative to the strength of the muscle at various joint angles versus machines that used a circular disc and the resistance remains constant despite joint angle. The results of the study showed an increase in peak muscle torque (13%) and power (20%) by the variable-cam group and 6% and 10% respectively for the disc group.

And although not statistically significant it should be noted that a greater increase in muscle circumference at rest was observed in the variable-cam group (1.7cm vs. 1.1cm Right arm and 1.6 vs. 0.9 Left arm). Read the full study here.

Unfortunately there are very few quality studies comparing variable resistance machines to free-weights.(1,2,3,4,5) However, of the research that does exist, most of the data points to a slight edge in strength gains for variable resistance and no significant difference in hypertrophy.

All Results being Equal

As I pointed out at the start of this article I don’t necessarily find machines to be superior to free-weights I just prefer them over free-weights. I use both because I believe variety matters for the purpose of having a well-balanced physique and I see the pros and cons of each. Research gives a small nod to variable-resistance machines for strength gains and hypertrophy is [for now] equal. So why my preference?

First, I value efficiency. Some people live to be in the gym, I live to get a result from it and then move onto other activities and interests (like writing these articles for you).

Second, I’m not a sadist but I relish in the deep fatigue and discomfort experienced when I can precisely target a muscle group.

Third, I like taking the skill out of the exercise so I can focus squarely on intensity of effort and training to failure without needing someone to spot me (I usually train alone).

Fourth, I love not having to rack my weights!

References

[1] Pipes TV, Wilmore JH.Isokinetic vs isotonic strength training in adult men.

Med Sci Sports. 1975 Winter;7(4):262-74. [2] Pipes TV.

Variable resistance versus constant resistance strength training in adult males.

Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1978 Jul 17;39(1):27-35. [3] Walker S1, Hulmi JJ, Wernbom M, Nyman K, Kraemer WJ, Ahtiainen JP, Häkkinen K Variable resistance training promotes greater fatigue resistance but not hypertrophy versus constant resistance training.

Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013 Sep;113(9):2233-44. doi: 10.1007/s00421-013-2653-4. Epub 2013 May 1. [4] Manning RJ1, Graves JE, Carpenter DM, Leggett SH, Pollock ML.

Constant vs variable resistance knee extension training.

Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990 Jun;22(3):397-401. [5] Boyer, B. T. (1990).

A comparison of the effects of three strength training programs on women.

Journal of Applied Sport Science Research, 4, 88-94.

For me the big picture is all about managing and manipulating training demands to stimulate muscle growth and strength at each stage of a person’s life. That means understanding how exercise fits within the schema of every other stress and activity a person is faced with and how to navigate the waters to help them reach their goals.

For me the big picture is all about managing and manipulating training demands to stimulate muscle growth and strength at each stage of a person’s life. That means understanding how exercise fits within the schema of every other stress and activity a person is faced with and how to navigate the waters to help them reach their goals. I was asked to write the forward for his book Muscle Explosion a few years back and the one thing I noted is that even though his training programs look bat shit crazy (and I mean that in a complimentary way), he is very calculated in his approach. He sees the big picture and then goes nuts mapping out the details.

I was asked to write the forward for his book Muscle Explosion a few years back and the one thing I noted is that even though his training programs look bat shit crazy (and I mean that in a complimentary way), he is very calculated in his approach. He sees the big picture and then goes nuts mapping out the details. If you’re not getting the result you want, reexamine the details and your application of them or adopt a new philosophy. Don’t jump on every new program or abandon what’s worked for each compelling piece of new information. Not without planning for it so you can determine its true worth and relevance to the big picture.

If you’re not getting the result you want, reexamine the details and your application of them or adopt a new philosophy. Don’t jump on every new program or abandon what’s worked for each compelling piece of new information. Not without planning for it so you can determine its true worth and relevance to the big picture.